An Overview of Ancient Fengshui

China, like its sister civilizations in Greece and India, developed a very sophisticated science of astronomy in its pre-classical period. Both solar and lunar eclipses are recorded on oracle bones from the mid-14th to the mid-13th centuries BCE. The most ancient extant record of a nova, or stellar explosion, is also contained in an oracle bone dating to circa 1300 B.C.E. The sighting of Halley's Comet was first recorded by Chinese astronomers in the classical period (467 BCE). And sunspots were observed without the aid of telescopes as early as 28 BCE. (Myths of sun ravens may be earlier references to this solar phenomenon.) While the Chinese did not have telescopes, they did invent other scientific instruments, and the following discussion will concentrate on one of them.

Neolithic Origins

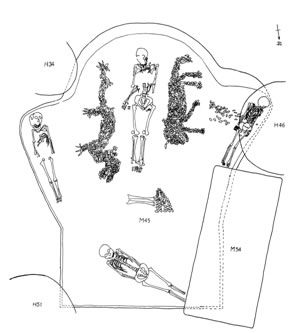

A neolithic grave unearthed recently in Henan province is a microcosm of the Chinese world as it was perceived at this early period. Its southern face (beyond the head of the skeleton) was round, while its northern face (at the skeleton's foot) was square, as in the illustration below:

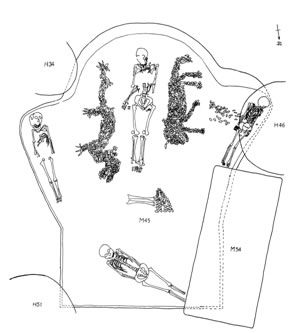

This accords with later images of the cosmos wherein earth was represented by the square body of a chariot and heaven by its round, umbrella-like canopy, as in this illustration:

More importantly, the remains of the body were accompanied by two figures outlined in shells, a dragon to the east and a tiger to the west. In the center of the grave was a representation of Bei Dou, the Northern Ladle (or Dipper). Since the dragon and tiger are also constellations in the Chinese sky, it is clear that the Yangshao people were already orienting their tombs with the annual revolution of the Big Dipper around the North Star.

The Cosmograph

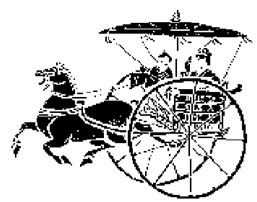

The oracle bones also record the names of four stars whose culmination marked the arrival of the solstices and equinoxes. Already in the 14th century BCE we see the nucleus of the Four Celestial Palaces, whereby the celestial equator is divided into four equal sections. Although seven constellations on this great circle are mentioned in the Book of Odes (9th century BCE), it is not until the late Warring States period (403-221) that the names of the entire zodiac were recorded. The following illustration is the lid of a lacquerware chest discovered in a Warring States tomb:

Curled around the left border is a dragon, while a tiger crouches to the right. In the middle of the lid is a rough circle of 28 characters that name the constellations of the Chinese zodiac. In the middle of the illustration is the pictograph of a ladle, representing the constellation Bei Dou, the Northern Dipper.

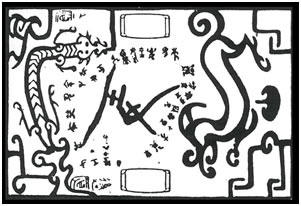

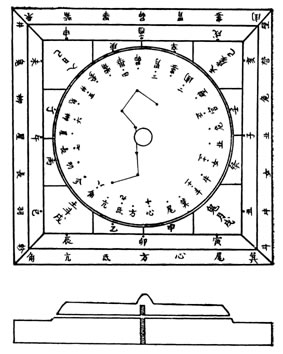

Finally, in tombs dating to the Former Han dynasty (206 BCE-25 CE), examples of the cosmograph were discovered, as depicted here:

Around both the square and round plates are arranged the names of the 28 constellations of the Chinese zodiac. The twelve months are arranged by decimal number counterclockwise inside the ring of the heaven disc, while the twelve Earthly Branches--a duodecimal numbering system--representing double-hours of the 24 hour day, occur clockwise on the inner square of the earth plate. In the center of the disc is a representation of Bei Dou, the Northern Dipper. Moving the disc to the right would represent the rotation of the Big Dipper clockwise around the North Star. If one observes the southern sky at the same time each night for several nights in succession, the zodiacal constellations will appear to move toward the west. The dial of the cosmograph as it is rotated clockwise on the earth plate corresponds to the arc made by the stars as they pass toward their setting in the west. The dial is obviously a stylized depiction of the same cosmology represented on the lid of the chest above.

The Four Celestial Deities

What is missing from the heaven disc of the cosmograph are the images of the celestial dragon and tiger. In the following illustration of the dome of heaven I have supplied outlines of the four celestial deities recognized by the Chinese--zhuniao, the Crimson Bird, canglong, the Cerulean Dragon, xuanwu, the Dark Turtle, and baihu, the White Tiger, which are macro-constellations each composed of seven of the 28 zodiacal constellations:

In any given season only one of these macro-constellations can be observed in its entirety in the night sky. In the ancient period the central constellation of each of the four deities occupied the center of the southern sky on the solstices and equinoxes. For example, on the summer solstice the Fire Star, the central star of the Heart of the Dragon, culminated at dusk.

The function of the ancient cosmograph can only be surmised since very few records of its use survive. The instrument is similar to a planisphere which allows the user to locate any star or constellation in the sky at any moment of the year. But more likely it functioned as a sort of cosmic clock. Ancient Chinese astronomers were fully aware that the quarterly (six-hour) diurnal rotation of the heavens was equivalent to the seasonal (tri-monthly) annual revolution. With a knowledge of what star was passing the meridian at sunset, a quick glance at the cosmograph could tell what constellation had culminated at noon or which one would be culminating at midnight. Or, knowing that a particular constellation had risen at sunset on the vernal equinox, a person would know what constellation was rising, culminating, or setting on the summer solstice. More importantly, perhaps, the disposition of the Dipper's handle could be predicted. The Dipper was the throne of Shang Di, the High Lord, the supreme deity in the Chinese pantheon, and the handle indicated the focus of his power.

I mentioned earlier that only one of the four palaces could be observed in its entirety in any given season of the year. This is because the celestial equator--the circular route traversed by the 28 zodiacal constellations--is not equivalent to the terrestrial equator or the horizon. The former is canted upward from the latter like the nested rings of a gimbal (one example of a gimbal is the rings of the "spaceship" in the movie Contact). Half of the celestial ring is above the horizon toward the south, and half is below the horizon toward the north. The Northern Dipper, on the other hand, which is closer to the pivot of the heavens--the North Star, is always visible in its complete revolution of the northern sky:

It is the location of the observer in the northern hemisphere that accounts for this phenomenon. The lower the latitude, the higher is the zodiac in the sky. At the highest latitude--on the North Pole, the celestial and terrestrial equators are equivalent. Here the North Star is directly above the observer, and the zodiac travels around the horizon. This is the situation idealized by the illustration of the dome of heaven above, and simultaneously by the cosmograph.

The Four Terrestrial Forms

So what does this ancient cosmology, and particularly the astronomical and astrological cosmograph, have to do with fengshui? Those with even a cursory knowledge of fengshui will recognize the dragon and tiger as the terrestrial models of the land forms to the east and west, or to the left and right, respectively, of the site being oriented by the fengshui master. A passage from the Book of Burial, the earliest extant work on fengshui, reads as follows.

The Dark Turtle hangs its head,

The Crimson Bird hovers in dance,

The Cerulean Dragon coils sinuously,

The White Tiger crouches down.

This verse is quoted from an even older text that is no longer extant, but which upposedly dates from the Han dynasty. In the period of time between the crafting of the lacquerware chest and the writing of the Book of Burial, a space of some six or seven centuries, the celestial deities came down to earth. There is no record in any ancient text of this transformation. We must ask ourselves how and why this change transpired.

Returning now to the cosmograph, we notice again that around the square earth plate (as well as around the circular heaven disc) are arranged the 28 zodiacal constellations. As we have seen, the disc represents a view of the heavens that is only visible from the North Pole, a situation that no ancient Chinese astronomer could ever have observed. Yet it is not the real world that is being modeled here; it is the ideal world.

In ancient Chinese myth there is the tale of a primordial battle. Previously the circular Heaven was separate from the square Earth and was supported by eight great mountains in each of the eight directions. When the water demon Gong Gong fought with the fire god Zhu Rong, he toppled the northwestern piller, Mount Buzhou, causing Heaven to fall downward and Earth to tilt upward in the northwest. After this catastrophe the rivers of China from that moment on flowed southeastwards, and the stars flew toward the northwest. It is the ideal world existing before the great flood that is captured by the cosmograph. The fact that these instruments were placed in tombs to accompany the deceased in the afterlife attests to their numinous quality. Rather than merely representing the ideal world, the cosmograph was a divine instrument that connected the two realms.

In the ideal world the four celestial deities of the dragon, tiger, bird and turtle, do indeed meet the earth as they traverse the horizon. The permanent situation captured on the earth plate of the cosmograph--dragon to the east, bird to the south, tiger to the west, and turtle to the north--represents the spring equinox. In many ancient cultures, including China, this marks the beginning of the New Year. When the cosmologist was replaced by the fengshui master in the centuries during and after the Han dynasty, the cosmograph slowly evolved into the compass, an unmistakable Chinese invention, and the function of the instrument evolved from celestial to terrestrial divination. But the purpose was unchanged. The hope was that humans might recapture the perfection of the ideal world. When he locates the dragon and tiger in his local environment, the fengshui master has discovered a veritable heaven on earth.

Fengshui and Qi

In its earliest form fengshui was utilized to orient the homes of the dead rather than the homes of the living. The term itself appears first in a passage from the Book of Burial which dates to no earlier than the 4th century CE.

Qi rides the feng (wind) and scatters, but is retained when encountering shui (water). The ancients collected it to prevent its dissipation and guided it to assure its retention. Thus it was called fengshui. According to the laws of fengshui, the site which attracts water is optimum, followed by the site which catches wind.

So what is qi? Thousands of pages of commentary have been dedicated to the explication of this term and, quite frankly, no English translation can do it justice. While "energy" may capture some of its physical characteristics, such a word does not address its metaphysical qualities. The Book of Burial characterizes it as "life breath." In one of its earliest contexts (The Zuo Commentary, 541 B.C.E.), qi is a meteorological category composed of the six phases of cold, warmth, wind, rain, darkness, and light. While it originally meant steam or vapor (as in clouds), by the time of Confucius it had come to mean an animating force in the atmosphere (manifested in weather phenomena) that actively influenced the human body (manifested in fever, chills, delusions, etc.). The science of fengshui analyzed this force in the environment with the intention of controlling its manifestations in the individual. Such analysis was scientific only insofar as it was based on empirical observation. When other factors such as numerology and astrology were consulted, fengshui became less a science and more an art. The "art" of fengshui derives little or nothing from the elemental, physiological plane but requires adherence to a belief in something like a force of destiny or fate. Borrowing the less than appropriate Western term, "geomancy," and adapting it to the Chinese tradition, we might refer to the art and science of fengshui as "qimancy," divination according to qi.

The earliest textual reference to the practice of site selection occurs in various similar passages on oracle bones dating from the middle of the Shang dynasty (1766-1046 BCE). Royal diviners queried Shang Di, the High God, by interpreting cracks appearing in heated animal bones. Here is an example of the pattern as it occurs on oracle bones.

On such-and-such a day, a crack was made. So-and-so divined: "The king would build a city; does the High God assent?"

In this example the gods are being consulted regarding the efficacy of a particular time for establishing a city, but the same method of divination was also used to determine the efficacy of a particular place.

The earliest textual reference to such al practice comes from the Book of Odes, the oldest anthology of poetry in the Chinese tradition. In a cycle of poems praising the exploits of the illustrious ancestors of the Zhou dynasty (1046-256 B.C.E.) the hero Gong Liu appears. Chief Liu led an exodus of his people to the fertile lands of Bin in the year 1796 BCE, according to tradition. The poem recounts the founding of his new domain, and this excerpt shows him conducting a geophysical survey.

Great was Chief Liu—

He surveyed the breadth and length of his lands;

He measured the shadow and observed the hills,

Noting the sunshine and shade.

He located the streams and springs. . . .

Liu was measuring the shadow of the gnomon, or sundial, to determine the cardinal directions. Sunshine and shade are the original meanings of the well-known terms yang and yin, which appear here in one of their earliest textual references. With this information he could determine which side of the hills and vales received the most sunshine during the winter, as well as the proximity of these sunny dells to sources of water. Such knowledge was crucial for an agrarian tribe that claimed to have descended from the demi-god, Prince Millet.

With these two bodies of evidence--archaeological records of Neolithic China and literary records of legendary China--we can already see the general outline of ancient fengshui:

It is this last point that demands our further attention. Astute readers will recognize in these two categories the origins of what eventually became the two major schools of fengshui, the Lifa or "Cosmological School" (a.k.a., "Compass School") and the Xingfa or "Form School."

The School of Kanyu

The earliest organized school of fengshui was known as Kanyu. The locus classicus for this term is the astronomy chapter of the Former Han dynasty (206 B.C.E.-25 C.E.) Daoist text, Huainanzi. Here is the passage in question: “On the kanyu the male is slowly moved in order to know the female.” From its context in the Huainanzi it is clear that some type of astronomical instrument is being manipulated. It may be the shipan, or cosmograph--an ancient planisphere--that is indicated here, models of which have been discovered in Han dynasty tombs. The specific meaning of kan is "canopy" and that of yu is "chassis"--reminiscient of the chariot illustrated above--in which case the term would mean "heaven and earth" or the "cosmos."

As regards the cosmograph, kan would refer to the rotating circular disc--the male component--and yu to the square base plate--the female component--as illustrated above.

By means of the cosmograph the configuration of the heavens could be determined at any time of day or night for any month during the year. First, the cosmographer would orient the earth board to the cardinal directions, represented by the four sides of the board. Then he would align the number of the month on the heaven disc with the double-hour of the day or night from the earth plate. Finally he would note the constellations on the portion of the disc that fronted the southern edge of the board. These are the asterisms that would appear in the sky in the month and hour of the query. In like manner the direction in which the handle of the Dipper is pointing could be determined. The ancient Chinese believed that the Dipper was the chariot of Shang Di, and the handle represented the focus of his celestial power.

Readers may wonder what part the ancient cosmograph played in the location of auspicious sites. Each of the 28 constellations of the zodiac corresponded to a particular earthly region, as did each of the Earthly Branches and, later in the tradition, the eight trigrams of the Yijing, the five elements or phases, etc. Time and space were thus joined in a prognosticatory system that enabled one to choose a fortunate location for a particular time or a fortunate time for a particular location. The cosmograph is more astrological than geophysical, perhaps, but later accretions would slowly transform it into the familiar luopan, or qimantic compass, of which it is the obvious precursor. The School of Kanyu, therefore, which was one of the first to make use of this proto-compass, is the ancestor of the Lifa school of medieval Chinese fengshui.

The earliest textual reference to a concept underlying the theories of the Xingfa, or Form School, of fengshui occurs in chapter 39 of the Guanzi, which dates to no earlier than the 5th century BCE. The passage in question reads as follows: “Water is the blood and breath (qi) of the earth, flowing and communicating as if in sinews and veins.”

Not until the 4th century C.E., in the text of the Book of Burial do we see a fully developed theory of the disposition of qi in the geophysical plane. Quoting an earlier text, the Classic of Burial, which is now lost, but purportedly dates to the Han dynasty (206 BCE-221 CE), the following passage discusses the relationship of xing (form, shape, features) and qi:

The Classic says: Qi flows where the earth changes shape. The flora and fauna are thereby nourished. It flows within the ground, follows the form of the terrain, and pools where the terrain runs its course.

The Burial Book continues with this commentary.

Veins originate in lowland contours; bones originate in alpine contours. They wind sinuously from east to west and from north to south. When thousands of feet distant they are contours; when hundreds of feet nigh they are features. Contours advance and finish in features. This is called total qi.

The proper location of the "lair," or burial site, is where the "features finish," and a large portion of the book describes how to recognize these auspicious forms. Here for the first time in the textual tradition the Four Celestial Palaces of the Cerulean Dragon, the Vermilion Bird, the White Tiger, and the Dark Turtle (which originally named the four macro-constellations that compose the ring of the 28 zodiacal constellations) are brought down to earth. On earth these celestial forms delineate the terrestrial forms that occupy the directions of east, south, west, and north, respectively (or left, right, front and back when facing south), of the burial site. The Book of Burial continues:

The dragon and tiger are what protect the district of the lair. On a hill amid folds of strata, if open to the left or vacant to the right, if empty in front or hollow at the rear, life breath will dissipate in the blowing wind. The Classic says: A lair with leakage will harbor a decaying coffin.

From a passage cited above we learned that "qi rides the wind and is scattered, but is retained when encountering water," which was the locus classicus of the term fengshui. Here we see that the terrestrial features that block the wind are necessary to prevent the dissipation of the natural flow of qi in and along the ground. Flowing water, like wind, also attracts qi like a magnet, and the auspicious lair is one that encourages water to linger in its vicinity without stagnating.

The mention of wind and water brings the discussion full circle back to the definition of fengshui. The science of fengshui in its earliest recorded context specifically refers to the School of Forms. Terrestrial features serve to block the wind--which captures qi and scatters it, and channel the waters--which collect qi and store it. Fengshui may literally indicate "wind and water," but this is merely shorthand for an environmental policy of "hindering the wind and hoarding the waters." The science of fengshui, therefore is "windbreak-watercourse qimancy." The art of Kanyu, on the other hand, the precursor of the Compass School, relies strictly on astrology and numerology as a means of fathoming qi on a cosmic scale. While fengshui is local, kanyu is universal. Since the medieval period in China--the existence of competing schools notwithstanding--masters of fengshui were versed in the environmental science as well as the occult art. The term I have coined, qimancy, divination according to qi, applies to both.

© Stephen L. Field 2011